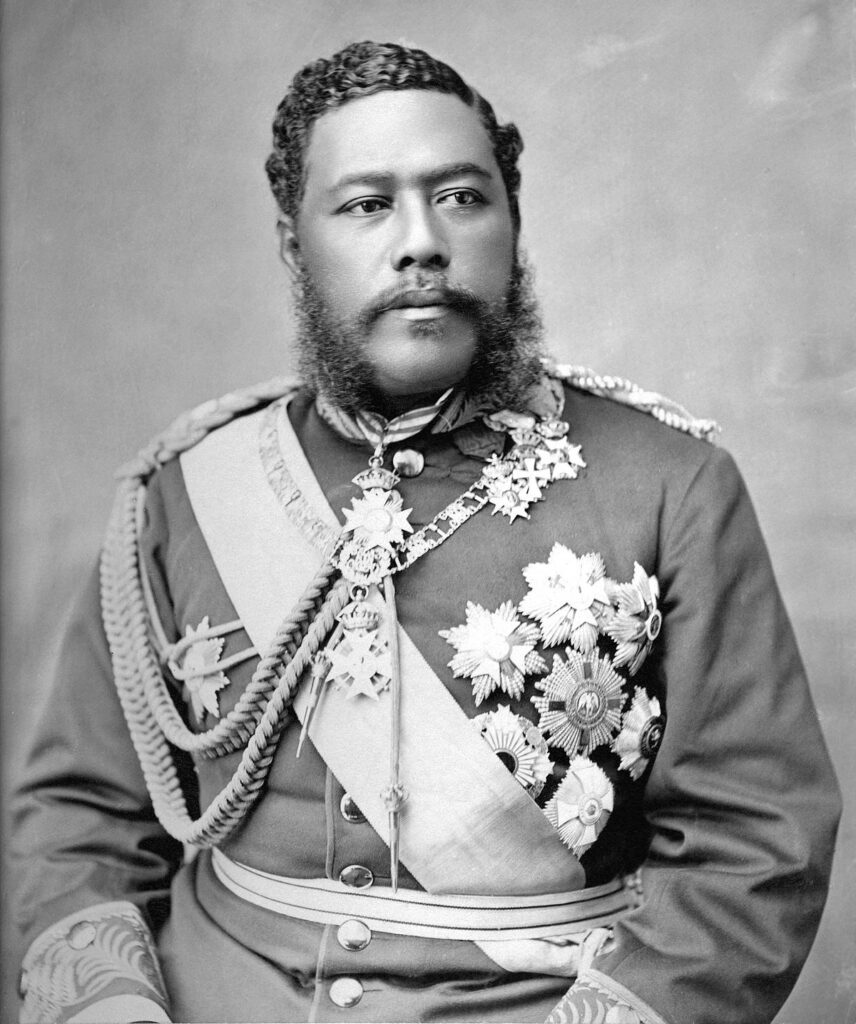

King David Kalākaua

King David Kalākaua

If ever there was a traveling man, King David La‘amea Kalākaua certainly earned that title in his era. In 1881, he became the first monarch to embark on and complete a journey around the globe. During his travels, he engaged with leaders across Asia, the Middle East, and Europe, using diplomacy to raise awareness about the Hawaiian Kingdom.

Before his reign, much of Hawaiian culture had been suppressed and outlawed. King Kalākaua sought to revive his nation’s cultural heritage by promoting traditional arts, medicine, music, and hula. This cultural revival period is often referred to as the first Hawaiian Renaissance, earning him the nickname “Merrie Monarch” for his vibrant and joyful disposition.

As a leader, King Kalākaua rekindled a sense of pride in Hawaiian heritage and culture. His passion extended to Freemasonry, where Brother Kalākaua was notably dedicated. He was one of the few monarchs in history, especially outside Europe, to serve simultaneously as Head of State and Master of a Masonic Lodge.

Childhood and Education

Kalākaua was born on November 16, 1836, at the base of Punchbowl Crater in Honolulu, on the island of Oahu. His parents, Caesar Kaluaiku Kapaʻakea and Analea Keohokālole, were members of the aliʻi class, Hawaiian nobility closely related to the reigning House of Kamehameha. His lineage traced back to Keaweaheulu and Kameʻeiamoku, royal counselors to Kamehameha I during the conquest of the Kingdom of Hawaii. Kameʻeiamoku, David’s grandfather, is one of the royal twins depicted on the Hawaiian coat of arms.

Kalākaua was one of seven children, with siblings including his older brother James and younger siblings Lydia, Anna, Kaʻiminaʻauao, Miriam, and William. Before his birth, his parents followed the Hawaiian tradition of hānai, a form of adoption, and had promised David to Kuini Liliha, a high-ranking chiefess. However, due to political conflicts, David was instead raised by another chiefess, Haʻaheo, and her husband, Keaweamahi Kinimaka. In 1843, upon the death of his adoptive mother, David inherited her properties, and his hānai father moved with him to Maui.

At age four, Kalākaua returned to Oahu to attend the Chiefs’ Children’s School (later renamed Royal School). Among his peers were his brother James, sister Lydia, and 13 royal cousins, including future kings Kamehameha IV, Kamehameha V, and Lunalilo. Known for his intelligence and amiable nature, Kalākaua learned English from American missionaries at the school. After completing his formal education, he studied law under Charles Coffin Harris, whom he later appointed Chief Justice of the Supreme Court of Hawaii in 1877

Military and Governmental Service

Before long, David’s military commitments took precedence over his legal studies. In 1852, Prince Liholiho (later Kamehameha IV) appointed Kalākaua to his military staff, and the following year, he joined the army as a first lieutenant in his father Kapaʻakea’s militia. By 1858, he had risen to the rank of colonel on Kamehameha IV’s staff.

Over the next 15 years, Kalākaua steadily advanced through various governmental roles. He served on the Privy Council of State and the House of Nobles, and worked in the Department of the Interior. In 1863, he was appointed Postmaster General and later served as the King’s Chamberlain until 1869, when he resigned to resume his law studies.

During this period, Kalākaua fell in love with Kapiʻolani, a young widow and lady-in-waiting to Queen Emma. They married on December 19, 1863, in a quiet ceremony conducted by an Anglican minister.

In 1866, the American author and fellow Freemason Mark Twain visited Hawaii and met Kalākaua. Twain spoke highly of him, noting:

“Hon. David Kalākaua…is a man of fine presence, is an educated gentleman and a man of good abilities…He is a quiet, dignified, sensible man, and would do no discredit to the kingly office. The King has power to appoint his successor. If he does such a thing, his choice will probably fall on Kalākaua.”

Rise to Power

When King Kamehameha V passed away on December 12, 1872, he had not named a successor. According to Hawaiian law, the absence of a designated heir required the legislature to appoint a new ruler. The 1873 election featured two prominent chiefs, Lunalilo and Kalākaua. Lunalilo won decisively but appointed Kalākaua as a colonel on his military staff. Throughout Lunalilo’s reign, Kalākaua remained active in national politics. Lunalilo, having no heir and failing to name a successor, died the following year.

Kalākaua’s popularity and his support for Lunalilo positioned him favorably for the subsequent election. Despite significant backing for Queen Dowager Emma, the widow of Kamehameha IV, Kalākaua won the Legislative Assembly’s vote by a margin of 39-6. He was sworn in the next day, which led to a riot by Queen Emma’s supporters. Lacking a standing army, the newly crowned king called upon American and British military forces docked in the harbor to suppress the unrest.

Reign as King & 1881 World Tour

Kalākaua’s priorities were reinvigorating Hawaiian pride in its culture and traditions and improving trade and the economy. Within a year of his election, he negotiated the Reciprocity Treaty of 1875, a free trade agreement between the United States and Hawaii that allowed products to be exported to the US duty-free.

He also became the first reigning monarch to visit America, attending the first White House state dinner, which was hosted by President Ulysses S. Grant. King David negotiated a treaty in 1875 which ultimately gave the United States exclusive use of Pearl Harbor to the United States. This treaty dramatically increased the kingdom’s income. In 1874, Hawaii exported $1,839,620.27 in products, which increased by 722% to $13,282,729.48, by the last year of his reign.

In 1881, King Kalākaua began a 281-day journey around the world to secure the importation of contract labor for Hawaiian plantations. The king first went to California and then sailed to Asia where he spent four months opening contract labor dialogue in Japan and China. His journey then took him through Southeast Asia and Europe, sightseeing and opening diplomatic and trade channels along the way. When he returned home, the nation celebrated his successful attempt at bringing global attention to his small nation.

King Kalākaua and Freemasonry

1874 was quite a year for Kalākaua. He had been a Freemason for years, and his involvement in the craft was well-known even before he took the throne. As the reigning king, he and his brother-in-law John Owen Dominis established the Ancient & Accepted Scottish Rite in Hawaii. Kalākaua and Dominis were the first 33° Freemasons in the Hawaiian Islands. That same year, King Kalākaua became the first Wise Master of the Nuʻuanu Chapter of Rose Croix. In 1876, Kalākaua served as the Worshipful Master of Lodge Le Progres de l’Oceanie, following in the footsteps of Alexander Liholiho (King Kamehameha IV) nearly 17 years later. Kalākaua went on to serve as High Priest of Honolulu Chapter Royal Arch Masons, No.1 in 1883, as well as Eminent Commander of Honolulu Commandery No.1, Knights Templar from 1876-1877.

1874 was quite a year for Kalākaua. He had been a Freemason for years, and his involvement in the craft was well-known even before he took the throne. As the reigning king, he and his brother-in-law John Owen Dominis established the Ancient & Accepted Scottish Rite in Hawaii. Kalākaua and Dominis were the first 33° Freemasons in the Hawaiian Islands. That same year, King Kalākaua became the first Wise Master of the Nuʻuanu Chapter of Rose Croix. In 1876, Kalākaua served as the Worshipful Master of Lodge Le Progres de l’Oceanie, following in the footsteps of Alexander Liholiho (King Kamehameha IV) nearly 17 years later. Kalākaua went on to serve as High Priest of Honolulu Chapter Royal Arch Masons, No.1 in 1883, as well as Eminent Commander of Honolulu Commandery No.1, Knights Templar from 1876-1877.

In 1880, Kalākaua received the Grand Cross of the Court Honor, the highest individual honor that the Supreme Council of the Scottish Rite of Freemasonry can bestow.

Several years later, the first formal dinner at the newly built ‘Iolani Palace was a Masonic event. He also converted part of the Palace’s attic into a Lodge meeting space and Masonic Temple. He notably leaned into Freemasonry during public events, mixing traditional Hawaiian imagery and rituals with Masonic symbols. When he traveled abroad, he sought Masonic temples and met with other prominent fraternity members.

Building ‘Iolani Palace

When Kalākaua ascended to the throne of Hawaii, he ordered the commission and the construction of a new ‘Iolani Palace, which remains the only royal palace on US soil. The cornerstone for ʻIolani Palace was laid on December 31, 1879, with full Masonic rites, and construction was completed in 1882. The Palace was the official residence of the Hawaiian monarchs, where they held official functions, received dignitaries and luminaries from around the world, and entertained often. Kalākaua selected December 31, 1879, Queen Kapiʻolani’s 45th birthday, for the cornerstone laying ceremony and tasked his Masonic brethren with overseeing the event.

The Hawaiian Freemasons organized an impressive parade for the cornerstone ceremony, one of the largest ever seen in Honolulu. During the event, they presented King Kalākaua with Masonic working tools, including a silver plumb, level, square tool, and trowel. When the palace was completed in 1882, Brother Kalākaua hosted a Masonic Gala with members of both Lodge Le Progres de l’Oceanie and Hawaiian Lodge.

Death and Legacy

Despite his declining health, King Kalākaua embarked on a voyage to California on November 25, 1890. Soon after he arrived in San Francisco, he suffered a stroke and was placed under the care of George W. Woods, surgeon of the United States Pacific Fleet. Despite his frail condition, Kalākaua insisted on attending his initiation into Shriners International on January 14, 1891.

A few days later, Kalākaua slipped into a coma and passed away on January 20, 1891, due to Bright’s Disease. His remains returned to Hawaii on January 29, along with the news of his passing, leading to the ascension of his designated heir, Liliuokalani. King David Kalākaua was interred at the Royal Mausoleum at Mauna ʻAla on February 15, 1891.

King Kalākaua’s reign ignited the first Hawaiian Renaissance, a revival of traditional Hawaiian culture. His enthusiasm for Hawaiian traditions fostered a renewed national appreciation for cultural heritage. After years of suppression, he reinstated the hula at his coronation, revived the Hawaiian martial art of Lua, and promoted surfing. His dedication to preserving and celebrating Hawaiian traditions and Freemasonry continues to inspire both his Masonic brethren and the Hawaiian people.